Logging in the Smokies

The History of the Little River Lumber Company & Railroad

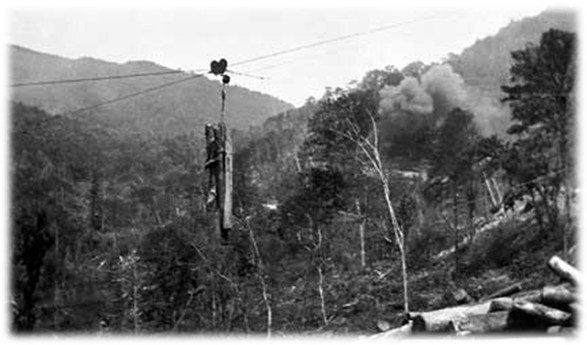

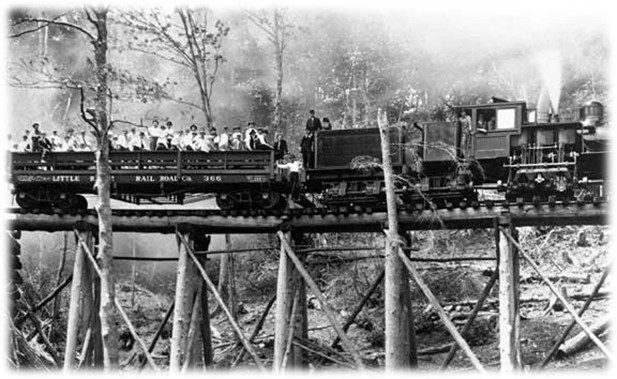

Railroad logging operations in the Smokies.

In 1901, Colonel Wilson B. Townsend founded the Little River Railroad and the Little River Lumber Company. The two were created to work hand-in-hand, bringing economic development to Tuckaleechee Cove. Before the boom of logging in the Smokies, the people of Tuckaleechee Cove and the surrounding communities in the mountains maintained a self-sufficient existence by farming the land.

The Smoky Mountains’ virgin forest drew the attention of logging companies in the late 1800s. The Little River Lumber Company bought over 80,000 acres of wilderness in what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The business plan was simple: Buy forested land, log it completely, and, once the area is logged, sell it. Railroads were set up to access the logging sites and transport the lumber back to Tuckaleechee Cove, where it would then be processed at the large mill. Clear-cutting was the method of logging used by the Little River Lumber Company. Clear-cutting is where an area of land is completely logged, leaving no trees left. This not only led to erosion of the land, but also to the destruction of many bio-diverse natural habitats.

Transportation of Logged Trees

Skidder in the Smokies.

Five main methods were used to transport the logged trees from their backcountry location to town. The first method involved using splash dams. Splash dams work by damming a small stream, making the water deep enough to float logs. The lumber was then cut and thrown into the stream. Once all the logs were at the dam, they would undam the stream.

This created a sudden flow of water down into the valley. The logs were then washed away downstream toward the railroad or town. The reason why the stream was flooded to begin with was because it would not have been deep enough to support transport of heavy logs. This method was quickly abandoned due to the terrain of the Smokies.

Another transportation method involved the use of a slide. A wooden slide would be built up-mountain to the logging site. As trees were cut, they would be placed on the slide to where a horse (or two) would pull the log down the slide by being chained to the ends of it.

Steam-powered skidders were also used in the transport of lumber. A skidder works with a system of cables and pulleys that are built between two points. A piece of lumber would be attached at both ends by these cables and, once connected, pulled down the mountain. This was a very dangerous practice, however, because the skidder would also pull anything the lumber got caught on.

To improve the skidder technique and to lessen the impact on the environment, an overhead skidder was mainly used instead. It worked just like the original plan, but instead the cables were suspended in the air. The piece of lumber would then “fly” through the air attached to these cables and safely be laid on a rail car.

Hanging bridges were a method that sometimes aided in the transportation. Railroad tracks would be laid, spanning a valley without any supports. No train engine would be on the bridge. Instead, rail cars would be filled with lumber and then guided down the hanging bridges by a steam-powered skidder. This transportation technique was mainly used to move logs in impassible terrain.

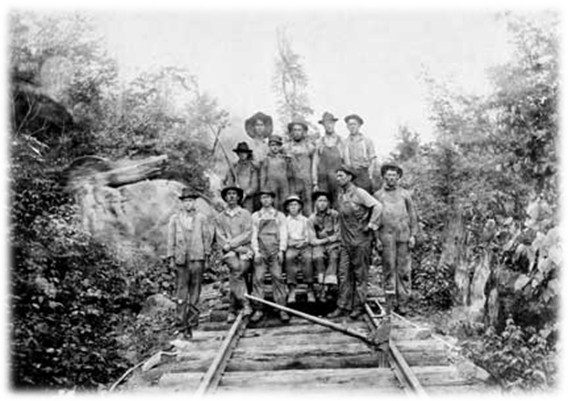

Railroad in the Smokies.

Laying the Tracks

Around 300,000 acres had been clear-cut by the middle of the 1920s. By this time, Colonel Townsend and his men had basically taken over the area of Tuckaleechee Cove, changing its name to Townsend in honor of him. The success of the logging industry was due in large part to the success of his railroad.

Before the tracks began to be dismantled in 1939, there were at least 150 miles of railroad. The beginnings of the railroad only consisted of approximately 11 miles – eight connecting Walland and Townsend, and three miles connecting Townsend to the forks of the Little River. Later on, another 15 miles were added to reach the area now known as Elkmont. As the logging continued, more track mileage was added to the railroad system.

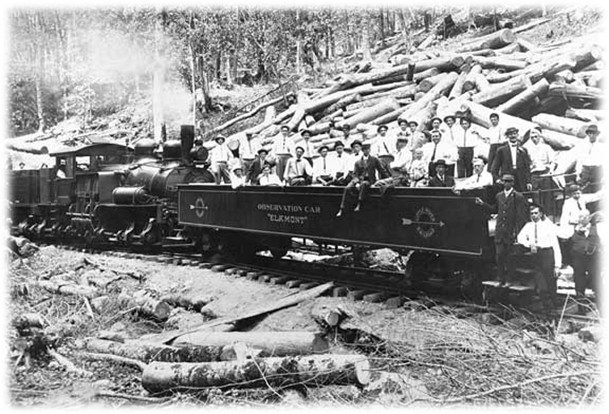

Railroad logging operations in the Smokies.

Shay engines developed by Ephraim Shay, who ran a logging business in Michigan, were the main source of locomotive the Little River Railroad used. They were able to hug tight curves and move up steep grades, perfect for mountain logging.

On average the company kept two locomotives, seven freight cars, five passenger cars, and four work train cars in stock. By 1939, it was estimated that over 150 million board feet of lumber were carried out by these engines. According to The Engineering Toolbox, a board foot equals 144 inches cubed (144x^3).

Logging Life

To most families in the area, logging provided a huge financial gain. Locals were hired by the company, clearing down trees in what was practically their own backyard. Logging communities were set up along the railroad lines leading up to the logging camps. Trains brought in setoff houses, a movable block-like dwelling that could be picked up and placed on a flat car and taken to the next site, if needed. These were truly the first “mobile homes.” Workers used these to live on-site, so when the job shifted a few miles down the track, the setoff house would be picked up, placed on a train, and set near the next logging site.

Logging life in the Smokies.

In addition to the setoff houses, Colonel Townsend built entire communities, including shops. Outside products and food were now being brought in to his workers, who couldn’t access them before. Self-sufficient farm communities soon became dependent on outside merchants and products brought in from the railroad.

Baptist and Methodist churches were also built in the logging communities and had ministers who were paid by Townsend himself. Easy life along the side of the railroad made for an increased work motive and improved lifestyle for Townsend’s employees.

Tourism Grows

As logging railroads began to make wilderness areas more accessible, tourism lines started making their way into the Smokies. Louisville & Nashville Railroad (L&N) passenger cars could easily fit on the Little River Railroad’s tracks. The tracks were constructed exactly the same as the others in standard gauge – 4′ 8.5″ in width – contrary to the tracks laid elsewhere in the area, which had a width of 36″.

Even though it cost the company 15 times as much to build a railroad, Townsend wanted to save time by not having to unload his cars. All he had to do was hook them up to another engine. Passenger cars could also be taken from other major railways and connected to his, providing tourists with access into the mountains. With the Little River Railroad lines connecting with other major transportation routes, tourism to the area grew significantly.

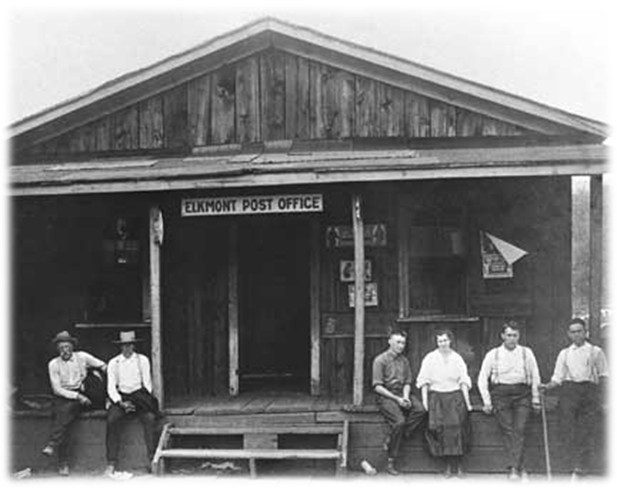

Elkmont Post Office.

With their love for the outdoors, people in Knoxville and other surrounding areas began to build summer homes and take vacations in the Smokies. Riding in observation cars was a treat, even though they were only flat cars with seats. Transportation was provided by the Little River Railroad lines. The former logging camps of Elkmont and Tremont were turned into vacation destinations, helping create hotels such as the Wonderland and clubs such as the Appalachian Club.

Later on, as the Little River Railroad began to dismantle its tracks, tracks leading to these vacation areas were taken up first. This was largely because having tourism lines occupying logging lines didn’t bring any profit for the railroad.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park was also pushing for these tracks to be removed. The tracks leading to Elkmont were some of the first to be taken up in 1926. Once the tracks were up, roads soon replaced them. By 1939, 560,000,000 board feet of timber had been sawed with the help of the railroads’ 150-plus miles of tracks.

Movement to Create a National Park

Railroad logging operations in the Smokies.

By the 1920s, many people began to take notice of how the logging operations in the Smoky Mountains were devastating the land. Ann Davis and others, including Horace Kephart, began to push for a national park in the area.

To push this movement, the Great Smoky Mountain Conservation Association was established. The only problem with advocating the idea of a national park was the fact that the land was mainly owned by individual residents and logging companies, including the Littler River Lumber Company, which did not want to leave.

In 1924, Colonel Wilson B. Townsend worked out a compromise with then-Tennessee Governor Austin Peay. The agreement allowed Townsend to sell all 76,500 acres of the land within the proposed park boundary, but still be able to log it for next 15 years.

Tremont Hotel.

During the Great Depression, buyers of lumber and other businesses which supported Townsend’s efforts began to go bankrupt. All the logging communities practically turned into ghost towns, and most of the resorts within the park began to empty out when World War II began.

In 1939, Townsend began dismantling the railroad tracks that were in the park, and he soon closed his business down as well. The main pathway into the Smokies for nearly 40 years had been removed, and the operations that brought attention to the Smoky Mountains in the first place were now out of its future forever.

For a more in-depth history of how the Great Smoky Mountains National Park came to exist, check out History of the Smokies: The People Who Lived There and the Development of the National Park.

Railroad logging operations in the Smokies.

For pictures and more information on the Little River Railroad & Lumber Company, check out The Little River Railroad and Lumber Company Museum located in Townsend, Tennessee.

All pictures used here are property of the Little River Railroad and Lumber Company Museum. Used with permission.