The Smokies: The People & The Development

On September 2, 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt stood at Newfound Gap, with one foot on each side of the North Carolina-Tennessee State line, and dedicated, “for the enjoyment of the people,” the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

On September 2, 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt stood at Newfound Gap, with one foot on each side of the North Carolina-Tennessee State line, and dedicated “for the enjoyment of the people” the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. A tremendous amount of time, labor, money, and desire was necessary to achieve this preserved area east of the Mississippi. Before the Smoky Mountains became a national park, average people from different walks of life (including the native Cherokees) lived in and made up the history of the area.

The Original Inhabitants

Before European Settlers came to the Smoky Mountains in their covered wagons, the Cherokee Indians reigned. A branch of the Iroquois, the Cherokee lived in the mountainous areas of the southeastern United States. Their society was based on hunting wildlife, trading, and practicing early agriculture. The Cherokee lived mostly in small communities that were situated around large streams in fertile valleys. Their homes were built with woven vines and other plants in a mud mixture fixated on wooden frames.

The government of the Cherokee Nation was fairly sophisticated in comparison with other native populations at the time. Each community or village had two chiefs – a Peace Chief and a War Chief. Both served no matter what state the community was in. The two chiefs did not wield absolute power, however; most of the decision making was made by tribal men and women who could voice their opinions during ceremonies and tribal meetings.

Cherokee women were actively involved in the day-to-day decision making of the tribe, which was something of a step ahead of the rest of the United States at that time. Every meeting was held in a seven-sided council house. The council house was designed to represent the seven clans of the Cherokee Nation – Bird, Paint, Deer, Wolf, Blue, Long Hair, and Wild Potato. Though the Cherokee were considered a primitive people, their democratic system of government system was very similar to that of the early United States.

Enter the White Man

The first European Settlers came to the Smokies in the late 1700s. Those settlers lived the same way the Cherokee did, hunting the wildlife and producing crops. For protection, the settlers chopped down trees to make houses and fences. Clearing the trees made room for further agricultural possibilities and wider roads. Average life for a settler in the Smokies included farming, hauling grain to the local mill, keeping up with the news, and attending church. Farming was done with only hand tools, such as shovels, hoes, and rakes. The more fortunate settlers owned an animal that could help plow the land.

Pigs were a main cash item in the Smoky Mountain area. Farmers preferred pigs over other livestock because they were largely self-sufficient animals. The pigs would eat anything in the wilderness, from acorns and plant roots to frogs and snakes. To help keep them from becoming wild, farmers would feed the pigs corn and other vegetables at one site. Settlers also liked the idea that rather than having to haul their produce to the store. The pigs could do it for them.

Raising cattle and sheep also played a huge role in the farming life of a European settler. Cattle and sheep were usually driven up onto the mountain trails to feast on the mountaintops. The high elevations reduced the number of flies, and the grass was more nutrient-rich. Over time, grazing on these mountaintops produced balds, where trees seldom grew. Evidence of this can be found today in the park by visiting Siler’s Bald, Andrew’s Bald, Gregory Bald, and other similar locations.

A general store could be found near every settlement. The local store provided settlers with everything they needed, from nails and farm equipment to even luxury candies. The store would also serve as a post office, handling letters written to other family members across the mountains. By providing out-of-town goods and serving the public, the general store quickly became a social gathering place, providing communities with “a place to go.”

Apple trees were abundant in the Smoky Mountains during the time of the early settlers. As a result, apples were a major part of the local diet. Besides eating fresh-picked apples, settlers found ways to preserve their fruit to last for long periods of time and into the winter months. Drying apples was a common practice. A bushel weighing 50 pounds could be dried, which would cause it to lose water weight. The end result would be a bushel with a total weight of seven pounds. The ability to turn apple juice into sweet cider, light fermented drinks, or even vinegar helped make every single apple worth harvesting.

Life in the Smokies was very harsh at times. The winter months were bitterly cold. Families lived in log cabins, and the cold wind could easily squeeze through the cracks and down the chimney. Snow fell heavily in the mountains, forcing people to stay inside their homes. To cope with loneliness and boredom, families would make quilts, read their Bibles, or strum and sing songs that they had learned or made up, perhaps helping give birth to early bluegrass music.

Cabin life in the Smoky Mountains was multi-generational. Grandparents, parents, and children lived in the same cabin, which sometimes consisted of only one room. Farming was the main staple in the way of life from spring to fall. In the winter months, the children went to school, since there was no extra help needed on the farm. The local schools in the area were almost all single-roomed, and the teacher taught all grades. The average education for a child in the Smokies was only three to five years – just long enough to learn how to read, write, and do simple math. The school teacher would board with a local family in the community that would help provide for her. The teacher would get paid $1 per child. Sometimes, if a family couldn’t afford to pay the $1, they would give the teacher some of their crops.

War Time

With the advancement of the early settlers, the native Cherokee began to become hostile to the white men. The settlers were taking over their land and forcing them out of their home areas. Even though the Cherokee desired the white man’s goods (such as firearms and farmer’s hardware), their way of life was threatened with the ever increasing westward expansion of the young United States nation.

In the early 1800s, the Cherokee Nation began to reform their own government. They established a more democratic style of government, consisting of a chief, a vice Chief, and a 32-member council that was elected by members of each tribe. A constitution and various laws were made. The Cherokee were trying in every way to tell the white settlers that they were on foreign soil.

It was during this time that a written Cherokee language consisting of 86 characters based off the sounds of the spoken language was invented. The system was invented by a silversmith and half-blooded Cherokee named Sequoyah. The Cherokee Nation adopted this as its official language in 1825. Shortly after the language was put in written form, a printing press with changeable type in the characters was ordered, giving birth to a Cherokee newspaper – The Phoenix. With its language available in written form, the Cherokee Nation now had a way to communicate with its people and other governments, such as that of the United States.

Regardless of the growth of Cherokee intellectualism, President Andrew Jackson put political pressure on the Cherokee to move out of their lands and into the lands of the west – specifically, Oklahoma and Arkansas. The conflict between the Cherokee and American settlers continued to rise until the signing of the Treaty of New Echota. The treaty was actually signed by Cherokee men who did not have authority, nor the representation approval, of the Cherokee Government. The treaty still stood, however, forcing the Cherokee to leave their homes and land. The six-month journey across the mountains, through the Tennessee Valley, and into Oklahoma became known as the “Trail of Tears” because of the many Cherokee who died from cold, hunger, and disease along the way.

Some Cherokee rebels decided to stand and fight, sometimes fleeing to the high mountain peaks to avoid capture. One of those men was called Tsali. Tsali became a hero in the eyes of the Cherokee and a terrorist in the opinion of the United States government, primarily because of his role in killing several soldiers. Tsali eventually surrendered to be executed in exchange for allowing some of the hiding Cherokee to be able to live in a plot of land located in western North Carolina.

This same land was also given to a group of Cherokee called the Oconaluftee, who helped the United States search for the rebels who chose to fight. The Oconaluftee also aided in the search for Tsali. The land had been given to them through the efforts of William H. Thomas, a North Carolina attorney, who fought for their right to live in the Smokies. Thomas represented the Cherokee in court for more than 30 years. Today, the land that was given to the Oconaluftee Cherokee and those that hid from capture is now called the Cherokee Indian Reservation. Unlike most western reservations, this one is completely open to the public and tourism-friendly industries.

A Civil War-era family.

A Civil War-era family.

The Civil War played a huge role in the shaping of society in the Smoky Mountain area as well. The communities on the Tennessee side were generally more supportive of the Union, while Confederate support was stronger on the North Carolina side. While the Smokies never saw any major engagements, minor skirmishes were fairly common.

Life Before the Park

Following the Civil War and throughout Reconstruction, the people of the Smoky Mountains continued their almost self-sufficient way of life. They produced their own food, sold their own goods, and prospered with almost no help from the outside world. Change did come, though.

Near the beginning of the 20th century, logging companies began to turn their interest toward the primitive old growth forests of the Smoky Mountains. Logging companies invaded the forest towns, employed the residents, and began to change things. Within 20 years, small logging communities such as Elkmont and Tremont had sprung up. People also became dependent on store-bought goods that were brought in with the logging companies. By the beginning of World War I, the Smokies were much more a part of the “real world.”

The Making of an Eastern National Park

Prior to the 1920s, nearly all of the nation’s national parks were located in the western United States. It was easier to form parks out west due to the lack of population there and the remoteness of the land. Plus, the U.S. government owned most of the land used to form those parks. Establishing a national park in the east was just too complicated because of the urban development and private land ownership. The land that made up the Smoky Mountains was owned by farmers, logging companies, and other businesses.

Willis P. Davis.

Willis P. Davis.

The original idea of an eastern national park came from a wealthy family in Knoxville, Tennessee. Mr. and Mrs. Willis P. Davis had traveled out west to see the great national parks and, upon returning home, asked themselves, “Why can’t we have a national park in the Smokies?”. Even though the Smokies was settled and logging was going on, there were a few people who owned land and used it for vacationing and hunting. The Smokies had a uniqueness of its own, and when people like the Davises started pushing for a national park there, the idea gained momentum.

As the Smoky Mountains began to attract more and more attention, logging companies started to combat the idea of a park being located there. Most of those who stood in opposition to the establishment of a national forest wanted the Smokies to be set up as a national forest instead. A national forest status would allow the logging companies and other businesses to stay, implying that this would be in the best interest of the people living there. National park status, however, would preserve everything from the trees to the streams and the wildlife within the mountains. In the end, the right people fought for national park status – and won.

Establishing a national park in the Smokies was far from easy, though. At least 300,000 acres of land in one large area had to be controlled by the government for a national park to even be considered. In 1926, President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill giving the Department of the Interior the responsibility of setting up national parks in both the Smokies and the Shenandoah Valley. With interest in seeing the idea of the park succeed running high in both Tennessee and North Carolina, the decision was made to place sections of the park in both states.

In 1927, North Carolina and Tennessee both contributed $2 million toward the creation of the park, but it was still not enough to purchase the land from those who owned it. In a last-ditch effort, Arno Cammerer of the National Park Service and Colonel David C. Chapman of Knoxville were able to persuade the wealthy Rockefeller family to donate financially to the creation of the park. The Rockefellers had promoted national parks in the west and had also contributed financially to their establishment.

Being sympathetic to the situation in the Smokies, the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Memorial Fund agreed to donate $5 million if – and only if – the states of Tennessee and North Carolina, as well as the park commission, would match the amount. In response, people donated money, school children pledged their pennies, and the states and the park commission came up with the necessary $5 million. In 1929, the National Park Service began to set out to purchase private lands within the suggested park boundary. Convincing area residents to leave, however, proved quite difficult. The people who lived in the Smoky Mountains had been there a long time – spanning several generations, in some cases.

It was the logging companies, however, that put up the most resistance to moving elsewhere. The Smokies had become the chief source of their financial gain. In 1930, condemnation suits began granting the states the right to condemn properties in the interest of higher use. Ironically, these residents of the Smokies would leave in tears just like the Cherokees who had inhabited the area before them. They accepted the money the government offered them for their land and began the process of seeking out new places to live. Logging companies agreed to deals which would let them conduct business in the Smokies until they could move their operations elsewhere. As an additional incentive, they received payment for any stock they had left.

The first park superintendent didn’t arrive on the scene until 1931. Major J. Ross and a team of park rangers reported for duty in June of that year. The National Park Service had finally come to the area, and, along with it, new government buildings built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. Most of the structures in the park were built by the CCC in a way to put unemployed men during the Great Depression to work. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt allotted $1.5 million to help assist with the purchase of additional property.

Condemnation of property continued until 1939. The government offered “life leases” to some of the elderly and sick who were unable to move. These life leases gave residents the freedom to live on the national park land until they died. In return, they couldn’t cut any timber, hunt, fish, or distort the environment in any way. These leases are a major reason so many abandon cabins and structures still stand today within the park. Finally, in 1936, the park acquired the necessary amount of acreage to establish a national park. With everything completed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt formally dedicated the Great Smoky Mountains National Park on September 2, 1940.

Contributors to the Founding

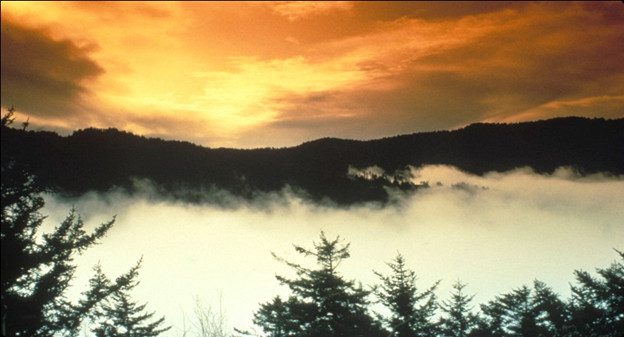

Sun over the Smokies.

Sun over the Smokies.

Several individuals contributed to the founding of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Davis family launched the idea of an eastern national park. Colonel David Chapman, president of a Knoxville drug company, pushed for support to located the park on the Tennessee side and even helped fund its establishment. Paul Fink explored many of the trails that are still used today and wrote about them in his journals. Fink also helped route the Appalachian Trail through the national park and other national forests in the area. Horace Kephart lived among the settlers of Hazel Creek and spurred the idea of a national park in the Smokies when he published his book Our Southern Highlanders in 1931.

George Masa who was an immigrant from Japan worked in photography and helped sell the idea of a national park through his photographs of the North Carolina side. Ben Morton, a former Mayor of Knoxville, Tennessee, sat on a committee that negotiated land settlements with major companies to leave the Smokies. Other significant figured included Mark Squires, a state senator from North Carolina who helped with the national park push, and Jim Thompson, a Knoxville photographer who kept people interested with his photographs on the Tennessee side of the park.

Charles Webb edited and co-published the Asheville Citizen-Times, a leading newspaper which helped convince people in North Carolina to support a national park and be just as excited about it as the Tennesseans were. In the end, though, it was every person who saw a vision of a preserved wilderness available to generations to come who made the Great Smoky Mountains National Park a reality.

And Now…

Visitors flocked to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park shortly after its dedication. The fact that it become one of the most visited parks in the U.S. ensured there would never be an admittance cost. As of today, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the number one most-visited park among those under the control of the National Park Service.

Unfortunately, the Smokies are getting even smokier these days due to the number of motorists who drive through them every year. This has resulted in the park seeking out new ways to combat pollution. One of the solutions so far is the creation of the Foothills Parkway, which encourages motorists to bypass the park lands and go directly to sight-seeing destinations outside of the park.

The formation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was an amazing process, and the area now stands as a museum to the people, for the people.